1: A high-level look at Linux components

1.1 Levels and Layers of Abstraction

- All components are arranged into levels or layers, groups of where said components reside between hardware and the user (i.e. is it low or high level?)

- E.g. web browsers are at the top layer, whereas the lowest layer has memory in the hardware - the binary code

- What makes up an OS are the many different layers in between

- A Linux system comprises of three main levels

- Hardware: memory, CPU(s) to compute and read/write to memory. Peripherals such as hard disks and network interfaces (STM32 wifi board) are also included

- Kernel: “core of the operating system”. Software which lives in memory and tells CPU where to look for its next task. The kernel is the mediator, managing hardware (especially main memory) and bridges the hardware and running programs

- TODO: relationship between kernel and firmware?

- Processes: running programs which the kernel manages compose the upper level; also user process

- IMAGE

- Kernel runs in kernel mode

- Code running in kernel mode has unrestricted access to processor and memory

- Powerful, dangerous permission; can corrupt and crash the system

- Memory which only kernel can access is called kernel space

- Kernel threads: look like processes but have access to kernel space, e.g.

kthreaddandkblockd- TODO: why are kernel threads used?

- Kernel threads: look like processes but have access to kernel space, e.g.

- User processes run in user mode

- Can access only a small set of CPU operaitons and memory

- Memory which only user processes can access is called user space

- E.g. if your browser crashes, it won’t also destroy your scientific computation program

- Theoretically, a user memory will not have the capability to damage the rest of the system; however, some processes are granted more permissions than others

1.2 Hardware: Understanding Main Memory

- Main memory is a big storage area for bits

- Kernel, processes, input, output all flow through main memory as collections of bits

- A CPU is just an operator on memory, reading and writing instructions and data from and to memory

- The term state refers to a particular physical arrangement of bits; e.g. process waiting for input or to finish computation

1.3 The Kernel

- Economics is all about scarcity

- Almost everything the kernel does relates to main memory. One of these is dividing memory into parts, always maintaining state information, making sure each process gets only its allocated amount of memory

- Kernel manages tasks in 4 general areas

- Processes: Which processes are allowed to use CPU

- Memory: Managing memory - what’s allocated to running processes, what’s shared, what’s free

- Device drivers: Acts as interface, or “mediator”, between hardware and processes; the kernel operates the hardware

- System calls and support: Processes use system calls to talk to the kernel

1.3.1 Process Management

- Starting, pausing, resuming, scheduling, terminating processes

- BOOK: Operating System Concepts, 10th edition (WIley 2018)

- Contrary to popular belief, processes do not run “simultaneously”. Although you may have a game and a spreadsheet open at the same time, they do not run at the same time

- Many systems may be able to use the CPU, but only one can use it at any given time

- Each process uses CPU for a fraction of a second, pauses, another process uses CPU, pauses, and repeat; the act of one process ceding control of CPU to another process is called a context switch

- Each piece of time, a time slice, will allow a process enough time to do its computation. Time slices are tiny, so system appears to be multitasking to us

- The kernel is responsible for context switching. Here’s what happens in user mode when a process’ time slice has been consumed:

- CPU interrupts the current process based on its internal timer, switches into kernel mode, then hands control to kernel

- Kernel records current state of CPU and memory, which will be important for resuming (in the future) the process which was just interrupted

- Kernel performs any tasks that came up during preceding time slice, e.g. data from input and data, I/O operations, etc.

- Kernel is ready to let another process run. It analyses the list of processes ready to run and selects one

- Kernel prepares memory for the new process then prepares CPU

- Kernel informs CPU of the length of the new time slice

- Kernel switches CPU into user mode and hands control of CPU back to a new process

- On a multi-CPU system, the kernel doesn’t actually need to relinquish control of one single CPU; more than one process can run at a time. The steps however are the same for a context switch Recap: Kernel runs between process time slices during a context switch.

1.3.2 Memory Management

- The kernel must manage memory during a context switch. The following conditions must be satisfied:

- Kernel must have its own private area in memory which user processes can’t access (kernel space)

- Each user process needs its own section of memory

- Some memory in user processes can be read-only

- User processes can share memory

- User processes may not access the private memory of other processes

- System can use more memory than is physically present by using disk space as auxiliary

- QUESTION: Is this swap?

- Modern CPUs have a Memory Management Unit, or MMU, which enables a memory access scheme called virtual memory

- A process does not directly access memory by its physical location (it doesn’t know where); the MMU intercepts the access and uses a memory address map to translate the memory location from the process’ point of view into an actual physical memory location in the machine

- Kernel still responsible for intiailising and continuously changing the memory address map

- The implementation of a memory address map is called a page table

- TODO: Read more about memory address maps here: https://www.mathworks.com/help/matlab/import_export/overview-of-memory-mapping.html

1.3.3 Device Drivers and Management

- Devices are usually only accessible in kernel mode as improper access could damage/crash the machine

- QUESTION: Examples of this? Aren’t devices accessible in user mode (e.g. device manager)?

- Device drivers exist to uniformise the different programming interfaces in different devices

1.3.4 System Calls and Support

- Other kinds of kernel features are available to user processes

- System calls, or syscalls, perform tasks user processes are unable to do well or at all

- E.g. File I/O involves system calls

- Two system calls are crucial for understanding how processes start:

fork(): When a process callsfork(), the kernel creates a nearly identical copy of the processexec: When a process callsexec(program), the kernel loads and startsprogram, replacing the currently running process- All new user processes on Linux begin from

fork()andexec()(exceptinit) - When you enter

lsinto a terminal, the shell running inside the window callsfork()to clone the shell, then the new copy of shell callsexec(ls)to runls

- Besides system calls, psudeodevices can also be used by user processes to communicate with the kernel

- Note that user processes still use a system call to access a psuedodevice

- Pseudodevices look like devices to user processes; however, they’re implemented in software

- E.g. Kernel’s random number generator device (

/dev/random)- TODO: Search up what /dev/ actually is

- QUESTION: Why is /dev/random hard to implement with user process?

- Recap: System Calls are interactions between a process and the kernel, how they communicate with each other

1.4 User Space

- User space can also be thought of as the large chunk of memory for the entire collection of running processes

- Though all processes look equal to the kernel, they are separated into a service layer hierarchy. The following is only an approximation

- IMAGE

- Top level are large, high-level components the user interacts with

- Complicated with many moving parts, such as a web browser

- Middle level are medium-sized components web browser uses

- Domain naming caching server, mail, print, database services

- QUESTION: What is domain name caching?

- Domain naming caching server, mail, print, database services

- Bottom layer are small components consisting of small, simple utilities

- In general, if one component wants to use another, the second component is at or above the same service level

- Note that it can be difficult or even pointless trying to categorise components based on complexity

1.5 Users

- A user is an entity which can run processes and own files

- A user has a username. The kernel does not manage usernames, but identifies users with numeric identifiers called user IDs

- Users exist to demarcate permissions and boundaries

- Every user space process has a user owner, and processes are run as the owner

- A user may terminate or modify the behaviour of its own processes (notwithstanding specified restrictions), but can’t interfere with other users’ processes

- A user may own files and share them with other users

- In addition to real human users, a Linux system also has a number of other users

- E.g. root, the superuser or the admin; anyone who can operate as root is an administrator on traditional Unix systems

- Operating as root is dangerous as the system will let you do anything, even if the action is harmful

- E.g. Connecting to WiFi will not require root access

- Root still runs in user mode, not kernel mode

- Groups are sets of users

2. Basic Commands and Directory Hierarchy

BOOK: The Linux Command Line

2.1 The Bourne Shell: /bin/sh

- A shell is simply a program that runs commands

- Shell scripts are text files which contain a sequence of shell commands; they are the most important parts of the system

- All Unix shells derive from the Bourne shell

/bin/sh, and every Unix system needs a version of the Bourne shell to function - Linux uses an enhanced version of the Bourne shell called bash, or the “Bourne again shell”;

/bin/shusually links to bash shell- QUESTION: how is bash an enhanced version?

- Command line completion using tab…

- QUESTION: how is bash an enhanced version?

2.2.2 cat

- The

catprogram outputs the contents of one or more files, or another source of input (e.g. terminal). The syntax is$ cat file1 file2. It performs concatenation when more than one argument is supplied

2.2.3 Standard I/O

- Unix processes use I/O streams to read and write data

- Input stream may be a text file, a device (peripheral), a terminal window, or output from another process

- When running

catwith no args, the program reads from the standard input stream provided by Linux kernel rather than a stream connected to a file; this input stream is connected to the terminal - Many commands read from stdin if arg is not supplied

- Some commands always write output to standard output stream

- A third I/O stream: standard error (stderr?)

2.3 Basic Shell Commands

- ls

- cp

cp [list: files to copy] [destination]- mv

- Rename a file:

mv [old_name] [new_name]- touch

- Create a new file:

touch [file_name] - If a file with the name already exists, this only updates the file’s modification timestamp

- Create a new file:

- rm

- Permanently deletes a file:

rm [file_name]

- Permanently deletes a file:

2.4 File structure

..refers to the parent of a directory.refers to the current directory- cd

- Move to an address:

cd [address] - This is a shell built-in command

- Move to an address:

- pwd

- “Print working directory”

- Outputs address of current directory

pwd - Poutputs full path

- mkdir

- Make a new directory:

mkdir [dir_name]

- Make a new directory:

- rmdir

- Deletes an empty directory:

rmdir [dir_name] - Deletes a directory and its contents - WARNING! VERY DESTRUCTIVE!:

rmdir -r [dir_name]

- Deletes an empty directory:

2.4.4 Shell Globbing, “Wildcards”

- The shell can match simple patterns to file and directory names, the process known as globbing

- Substitution is known as expansion; the shell expands globs before running commands

at*expands to all filenames which start withat*atexpands to all filenames that end withat*at*expands to all filenames that containatb?atexpands to all filenames with?as arbitrary character' 'will cause the shell to not expand a glob

2.5 Intermediate Commands

2.5.1 grep

- Prints lines from a file or input stream matching an expression

- The following prints lines in

/etc/passwdfile containing textroot

grep root /etc/passwd- The following prints filenames and matching lines in

/etccontaining textroot

grep root /etc/*

grep [regex] [location] # general formatgrepuses regular expressions. The following are three important things about regex:.*matches any number of characters, i.e.*in globbing.+matches any one or more characters.matches exactly one arbitrary character, i.e.?in globbing

2.5.2 less

- Displays output of a file or command in pages

- The following pages through the file

/usr/share/dict/words

$ less /usr/share/dict/words

$ less -FX # this adds a paging system to the output- You can press

spaceandbto go forward and back, andqto quit - You can also search for text with

less- To search forward for

word, type/word - To search backward for

word, type?word - Press

nto continue searching

- To search forward for

- To send the output of a

greptoless:

grep ie /usr/share/dict/words | less2.5.4 diff

- Outputs difference between two text files

diff file1 file2

diff -u file1 file2 // another format?2.5.5 file

- Outputs file format of a file

file file2.5.6 find, locate

findlocates a file in a directory tree

find dir -name file -printlocateuses the same syntax, but searches an index (cache?) the system builds periodically instead of searching in real-time- TODO: What else is

findcapable of?

2.5.7 head, tail

- Shows beginning or end portion of a file

head /etc/passwd # displays first 10 lines of etc/passwd file

head -5 /etc/passwd # displays first 5 lines of etc/passwd file

tail +5 -5 /etc/passwd # displays 5 lines starting at line 5 of etc/passwd2.5.8 sort

- Sorts lines of a text file in alphanumeric order (not that useful…) with

-nandr

2.5.9 tr

- Basic output replacement

- TODO: Syntax?

2.6 Changing the Shell

- You can change the shell with

chshcommand

2.7 Dot Files

- Configuration files are usually hidden from

lsby default - To get dot files, use glob pattern

.??* - TODO: Why do people publish their dotfiles online?

2.8 Environment and Shell Variables

- The shell can store temporary variables, shell variables, containing value of text strings

- Some shell variables control the way the shell behaves, e.g.

PS1 - An environment variable is similar to a shell variable, but can be passed to other programs that the shell runs; shell variables can’t be accessed in commands that you run

- Child processes inherit environment variables from their parent. E.g. you can put a custom

lesscmd configuration in environment variableLESS; when runningLESS,lesswill run with those options

$ STUFF=blah # to assign a shell variable

$ export STUFF # makes shell variable into an environment variable2.9 Command Path

PATHis a special environment variable which contains the command path, or path. The path is a list of system directories the shell searches when locating a command- The shell will search each directory in

PATHfor the program, and runs the first matching program- E.g. running

lswill have the shell search directories until it finds anls

- E.g. running

2.91 Editing the Path through the command line

- To add a directory to the beginning of the

PATH:

$ PATH=dir:$PATH- To append a directory to the end of the

PATH:

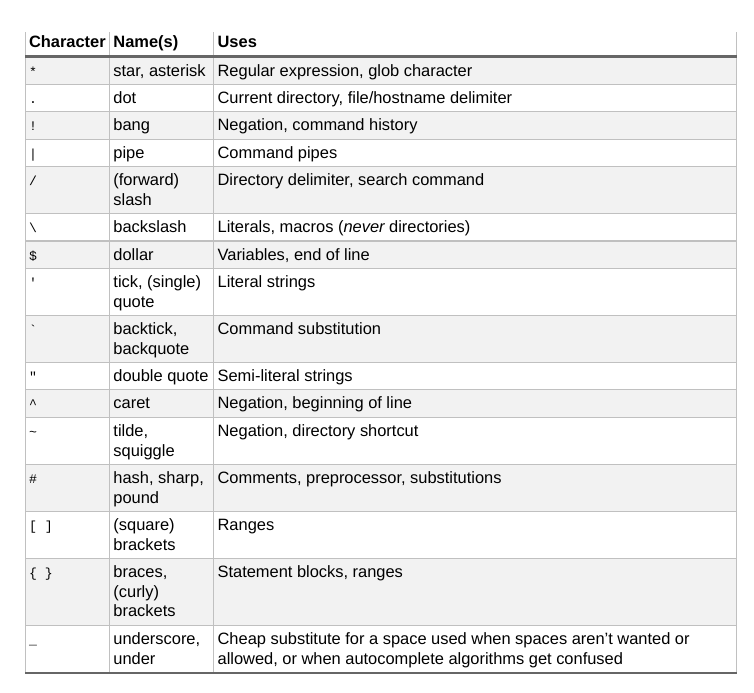

$ PATH=$PATH:dir2.10 Special Characters

- JARGON FILE: catb.org/jargon/html

- Commands using

ctrlwill be prefixed by a caret, e.g.^C

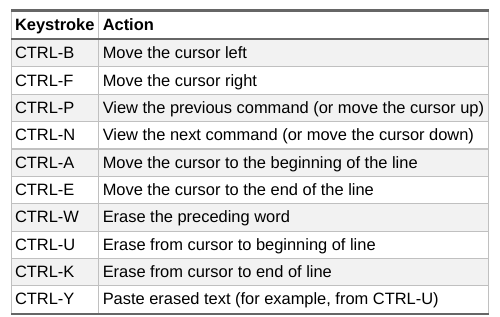

2.11 Command-Line Navigation

- It is much faster to edit on the command line with control key combinations

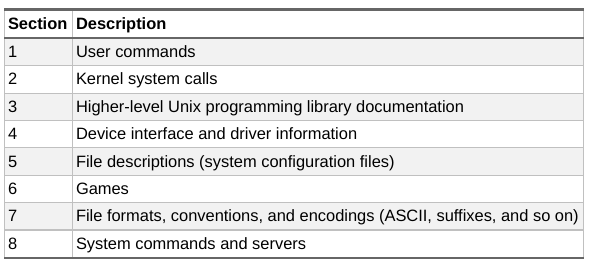

2.13 Reading the Manual

- To read the manual page for a certain command:

$ man ls

$ man -k [keyword] # this searches a keyword

- Sometimes there are conflicting term names. For example, to read the /etc/passwd file description instead of the

passwdcommand, one can insert a section number:

$ man 5 passwd- Another format called

infomay also be used:

$ info [command] | less2.14 Shell Input and Output

- To send output of a command to a file instead of the terminal:

$ command > file # overwrites file and creates file if not exist

$ command >> file # appends instead of overwriting the file- This is fairly useful to collect output in one place, e.g. when debugging a program!

- To send the output of a command to the input of another command, use pipe

|

$ head /proc/cpuinfo

$ head /proc/cpuinfo | tr a-z A-Z

# This send the output of head to tr, where it replaced all lowercase letter with # uppercase letters. This also caused havoc with floats...

# Add more | to send output to more commands2.14.1 Standard Error

- A standard error, or stderr, is an additional output stream

$ ls /fffff > file # yields No such file error